In the back of a fifteenth-century manuscript, Antonio Salutati–a factor for the Medici Bank–gave his recipe for lasagna. With this recipe, Salutati concluded his book of advice for young apprentice merchants. While the rest of the book focuses on the practical skills necessary to survive–and succeed–in the high-stress world of finance and trade (and most of it was not even by Salutati himself, but copied from an earlier merchant manual, written in the fourteenth century, by the Florentine merchant Saminiato de’ Ricci), this final section takes an unexpectedly personal–and psychological–turn.

Antonio wrote:

He who deals in exchanges and he who deals in merchandise is always anxious and beset by worries. I will instead give you a recipe for lasagna and macaroni.

For lasagna, you need three fat capons and a piece of beef; set them to cooking. In another pan, put the lasagna in boiling water, one at a time, and never stir. Grate some Parmesan cheese. When the lasagna are ready, drain them. Pour over them the fat from the capons and the beef and let it all stand, covered, so that the flavor penetrates -you’ll never have tasted anything so good.

For macaroni you do much the same.

Let him who wants to draw on Bruges and remit to Paris do it. I for my part prefer to enjoy supper with my companions. Amen.1

It is a famous passage, oft-cited by historians.

For Antonio, hospitality and companionship helped assuage anxiety and mitigate worry, especially in troubled and difficult times. Perhaps for men like Antonio, who made (or lost) fortunes at the edge of risk, all times are troubled and difficult times–but some are more troubled and difficult than others. Europe, in the early fifteenth century, was unstable. Beset by war, religious unrest, civic factionalism, political instability, currencies rose and fell, monarchs devalued them to fund wars, and there was a shortage of coin everywhere. Through it all, men like Antonio were expected to keep the money moving, circulating, free as the birds of the sky. But this frictionless movement was an illusion, conjured by men who knew (or thought they knew) the inner workings of the economy.

Italian merchants working in the late medieval and high renaissance periods (c. fourteenth through sixteenth centuries) left behind voluminous records of their economic activities. They wrote comparatively little about their own motivations for participating in this exhausting dance. “What was it all for?” Aside from a few famous exceptions, the answers to this question are almost all secondhand, derived from the books they read, the art they commissioned (or bought), the buildings that they built, and the churches they supported. So much of this material is oriented towards the afterlife. Antonio’s brief aside on the pleasures of good food and company represents a rare glimpse into the quotidian psychology of a fifteenth-century Florentine merchant. He doesn’t quite give us a description of what constitutes a good life, but he does set down, in writing, a concrete example of what kept him going, and what made life worth living in the moment.

*

I came across Antonio’s recipe for lasagna while I was in the middle of dissertation research. During the dissertation writing process–a period when I was often alone, by inclination and necessity–I thought of him often. I pictured him sitting at a table, basking in the warm glow of candlelight, surrounded by friends. A moment beautiful and fleeting.

*

Those living in our own troubled and perilous times would do well to heed Antonio’s advice. Hospitality and companionship help us weave the world we wish to live in. Tomorrow will always bring more trouble and worry. Friendship gives us the fortitude to say come what may, but until then, let us hold each other in the golden circle, in the present, let us gather together in a warm, well-lit room. For when we picture the good life, does anyone picture living it alone?

- Translation by Reinhold C. Mueller, The Venetian Money Market: Banks, Panics, and the Public Debt, 1200-1500 (Baltimore/London: Johns Hopkins Press, 1997), 355.

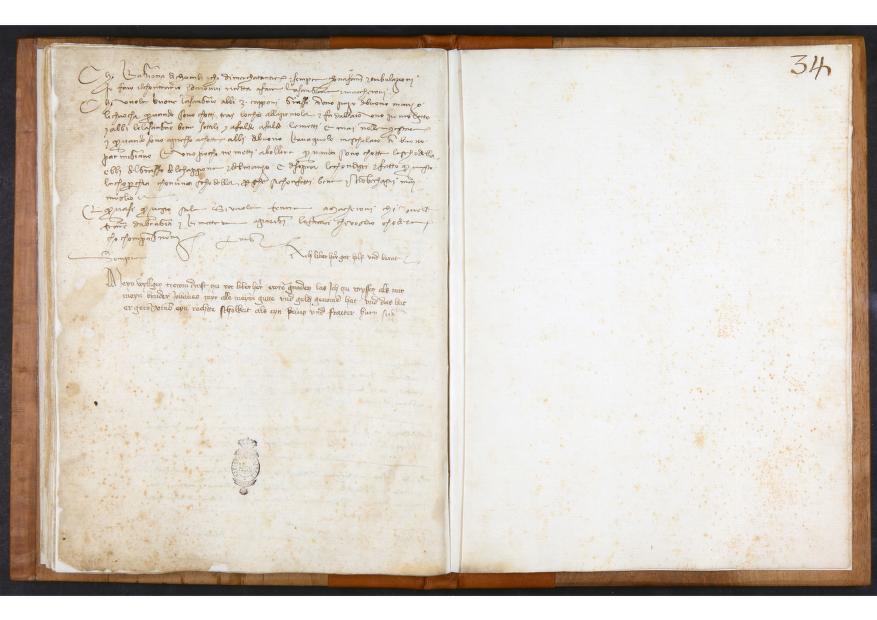

“Chi ragiona di chambi e chi di merchatantie sempr’è chon afanni e tribulazioni. Io farò il contrario e darovi ricetta a fare lasangnie e maccheroni.

Chi vuole buone lasangnie habbi 3 capponi grassi con un pezo di buono manzo. Li chuocha; quando son cotti trai l’occhio alla pentola, e fa da llato uno pentoletto; e abbi le lasangnie bene sottili, e a falde a falde le metti, e mai non le mestare; e quando sono apresso a chotte, abbi di buono ravagnolo mescholato con buono parmigiano, e uno poco ne metti a bollire. Quando sono chotte le schodella; ebbi del grasso del chappone e del manzo, e di sopra le chondisci, e fatto questo le coperchia con una schodella perché si confetti bene. E non bechasti mai meglio.

E quasi questo stile si vuole tenere a macheroni.

Chi vuole trarre da Bugia e rimettere a Parigi lo faccia, che voglio ghodere co’ compagnoni. Amen.” ↩︎