On our last visit to San Francisco, I squeezed in a vase glazing workshop at the Heath Clay Studio. Even though I spent a lot of time in graduate school studying the history of porcelain, it had never occurred to me to take a course in either ceramics or glazes, probably because most contemporary ceramics studios work with stoneware, rather than porcelain, and the two are very different materials.

The artist who taught our workshop was an amazing teacher, and he managed to pack so much information into a brief session, it made me wish that I had found the time–and resources–to squeeze in some hands-on education back when I was still working on the history of porcelain. (I also regret that I can’t give you the name of our wonderful teacher. I lost my notes from our workshop.)

Each student received an unglazed, bisque vase blank, to glaze as we saw fit. This kept us focused on the glazing process.

We learned a little bit about how glazes work–the differences between matte and glossy glazes, how glazes interact with each other when layered, how to manipulate the thickness of each glaze to achieve different effects.

Set free to experiment, some of us jumped right into the thick of things, dunking our vases into buckets with optimistic abandon. Others (like myself) studied samples, only approaching the glaze buckets after long deliberation. After all, we only had a single shot.

Our teacher made everything look easy. With one fluid motion, he dipped his vase into the glaze. The vase came out glistening, coated in a single smooth coat of color. When I tried to replicate the same motion, the glaze dripped and congealed. I wondered how many repetitions it would take to acquire the necessary muscle memory.

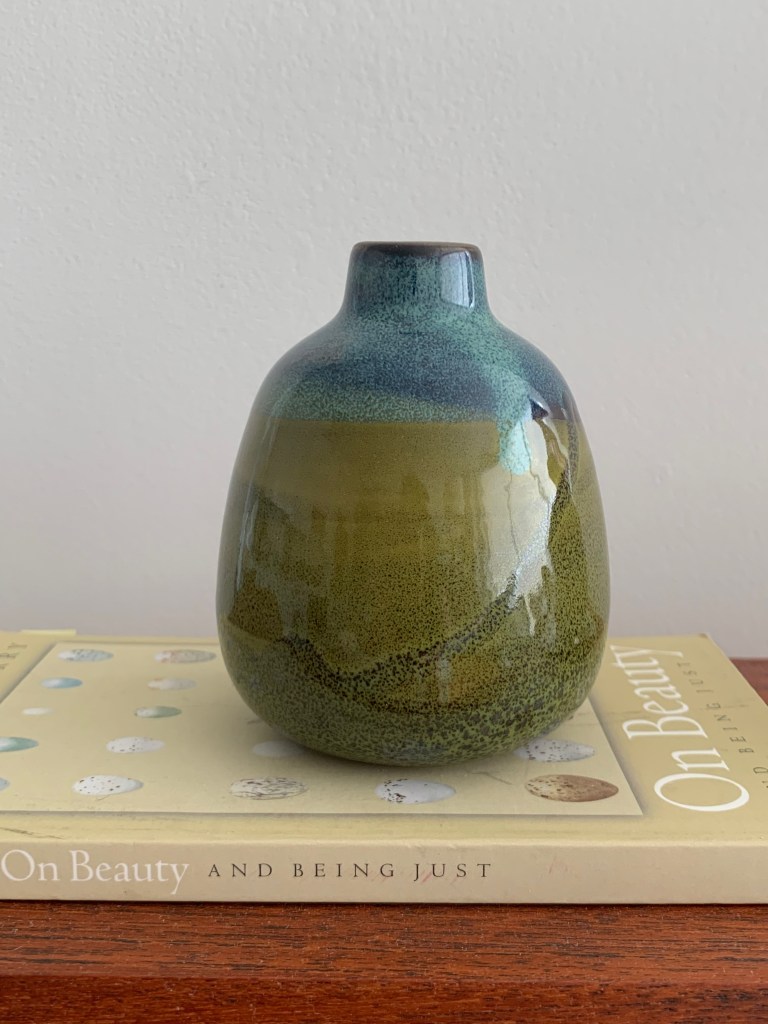

There was something thrillingly experimental about the process. Having no prior knowledge to draw on, I could only imagine my finished vase. I settled on a simple design. The entire vase would get a base coat of hematite. After that, I would divide the vase into thirds. The top third would receive a soft green glaze, almost the color of old copper. I chose a glossy yellow to layer over the rest of the vase. With luck, the hematite would show through the transparent overglazes, speckling the vase with dark, vaguely metallic spots.

I felt a strange satisfaction when I placed my vase on the tray set aside for finished pieces.

A few weeks later, a package arrived in New York. I unpacked my vase, and found myself pleasantly surprised. For the most part, it looked exactly as I’d pictured it, marred by one small flaw (a spot where too much glaze had gathered and congealed – a more experienced person would have wiped away the excess – but not me, for I didn’t know any better).

Now it sits in our living room, keeping company with two other bud vases.

Looking back, I wish I’d taken some ceramics classes while I was still studying the history of porcelain. I know, intellectually, how these things were done. I’ve watched videos. I’ve even visited workshops and kilns. But I’ve never done any of it myself. That body of knowledge remains, in many ways, dormant, because it hasn’t been (not yet, anyway) incorporated into my body.